Reading: Watership Down

I'm dusting the cobwebs off my blog, realizing that I had a couple unfinished book reviews waiting for me, I still have a couple on the backburner and yet here I am working on a new review. I'd previously reread A Clockwork Orange and also read Phantom of the Opera as well as The Island of Doctor Moreau for the first time. For the book club I'm running myself, we just wrapped up Watership Down by Richard Adams. This was a reread for me and also was a childhood favorite. It's the kind of book that a kid with a certain type of brain gets sucked into. Admittedly Watership Down was an obsession for me for a while.

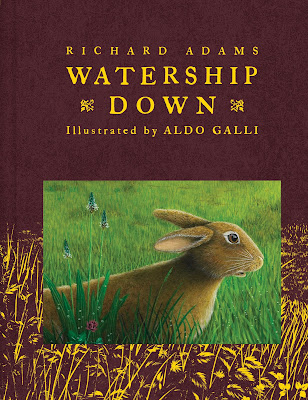

I read this wonderful illustrated edition of Watership Down which includes paintings by Aldo Galli in glossy inserts. Good stuff. Revisiting as an adult, I can really appreciate why this particular book has had such staying power. Along with being just a fantastic and epic tale, Watership Down is also impeccably researched both for the behaviors and nature of its rabbit characters as well as the ecosystem they fit into. To any young lover of nature, the book is a captivating exploration of the natural world through a fantasy lens. Adams takes great care to be accurate to how rabbits behave in order to immerse us in their perspective and understand it. He also takes great pains to show how they interact with the world around them and makes sure that their actions feel reasonable and within their means. Of course, they are somewhat anthropomorphized, in that they have language, story-telling and culture that is akin to ours in some ways, but the feeling is very much "if this animal could talk, what would it say?" Adams also invents a language with its own terms for specific rabbit experiences and behaviors.

What I also felt was very grounding and well-done was the choice to have the book take place in a real place. All the locations of the book were apparently local and known to the author and how the rabbit characters navigated that landscape was quite detailed. It also gives us, the reader, a funny sense about the scale. What is merely an expanse of mere miles (a short drive) for humans is a massive undertaking for the rabbits and we feel both the enormity of their journey and understand the difference for us.

I was recently talking to a friend about the way a lot of xenofiction (ie: fiction from the perspective of non-human characters, often animals) misses the mark due to the author not researching the animal characters whose perspective the story is in while attempting to ground the book in some sort of reality. Animal stories don't always have to be realistic, mind, many stories that aim more for the symbolic can be wonderful, but it can definitely take a reader out of the story when they bump up against an element in the fiction that does not at all match their knowledge of the animal. One thing that always takes me out of the fiction is when any animal species is represented as quintessentially evil and another is when the animal characters are bound by stereotype or disproven theory (for example the alpha structure of the wolf pack which was only a behavior observed in captive wolves, not in the wild). Watership Down hits the mark exactly for embodying a non-human perspective.

The story begins with Hazel and Fiver, two young rabbits in a large warren. Fiver has prophetic and terrifying visions of a great danger coming to the warren and tries to warn the others that they must leave. Hazel, knowing that Fiver's visions have some merit to them, manages to round up a small group of rabbits to leave with them, while the governing structure- the Chief rabbit and his guards, the Owsla- dismisses any concern. The rabbits make a perilous journey to find a new home, braving wilderness, wild predators, and experiences that are alien to them.

Mythology and story-telling plays a huge role in this book. The rabbits have a religion of sorts, a creator myth of the Sun god Frith and of the Prince of rabbits El-ahrairah, whose stories of trickery and mischief live on through an oral tradition among rabbits. The El-ahrairah stories tell of the many enemies of rabbit-kind and all the ways that the cunning prince outsmarts and outruns them, as well as stories of clever heists of vegetable gardens and other acts of mischief. These stories, it turns out, are as much traditional tales as they are a mythologizing of personal adventures, with a reveal at the end of book that the Watership Down rabbits' own incredible journey becomes an El-ahrairah tale. I am also reminded of the various coyote stories from several indigenous peoples of North America, where in some tales coyote is a trickster, a benevolent figure, or both.

Aiding the sense of myth and a connection to mythical archetypes are quotes from various sources at the beginning of each chapter, which relate to the events of said chapter. Adams pulls from history, literature, plays and poetry in a way that really makes the whole story feel grand and epic.

The rabbits in their journey to Watership Down, the eventual home that they find and end up having to defend, encounter a series of dangers that they end up needing to outsmart. Hazel, who becomes the leader of the ragtag bunch, saves his companions thanks to both his own cleverness and his willingness to listen to the input of the others. Along with his willingness to take advice from his companions, he also sees value in other creatures (animals share a common rudimentary language separate from their own native tongue) and ends up recruiting help from both a mouse and later a gull who both prove invaluable.

What's interesting is that we see different types of societies in the story too. One of the warrens they encounter on the way to Watership Down is a decadent society, somewhat akin to the Lotus Eaters encountered in Homer's Odyssey, or that of the delicate Eloi in HG Wells The Time Machine. These rabbits are beautiful, healthy, and carrying a dark secret that they keep in exchange for their decadence and relative safety. The other society encountered is Efrafa, a fascist society controlled by the tyrannical General Woundwart. Both societies foster behavior that is not natural to rabbits, both in exchange for safety. By contrast, Hazel and his rabbits live a more risky but democratic life, with value placed on community and freedom that is not at the expense of others. The book definitely strikes me as more political than it did to me as a child, both in terms of its societal and government critiques as well as the very blatant ecological message.

On the note of ecology, man's relationship to nature is something that's explored intently- showing the ways that human existence effects animals (not always negatively but there's no doubting that we change their lives significantly). The casual cruelty of men is highlighted too in the ways that feel all the more disturbing while we share the rabbits' perspective- shooting any animal because it's where it "shouldn't" be. I think this book really serves as a kind and meaningful reminder that wild animals and nature are all around us, even in areas that are "ours", and we should take care to coexist with it.

I will say, Watership Down is definitely a tense and gripping book, filled with the fear and uncertainty that prey animals need to survive. In a lot of ways, it's a rough read, and it surprised me that even revisiting as adult I still found my heart pounding at critical points of action and peril. You might find yourself crying over the rabbits but in a way that I don't find maudlin or tacky. The action is tense but not everything is hopeless or without its balance of joy. You will grow to love all the rabbits, their quirks, their story-telling, their humor, their cleverness, and be invested in their ability to keep running from danger. I was particularly fond of Bigwig, a brave and strong rabbit who befriends the gull Kehaar, and whose actions end up saving many rabbits.

All in all, a book I recommend. A great adventure for kids, but a rich fantasy classic for adults too. Part of its strength is in my opinion, that Adams started this book first as stories he told to amuse his own children. There's very much the flavor of story-telling and oral tradition in the book, and a sense that it's meant to be captivating and exciting for an audience.

Also, as mentioned by my friends in book club, you could absolutely teach a whole college course about this book to explore myth, symbolism, archetypes, and all the quotes tied to each chapter.

.png)

Comments

Post a Comment